ALBANIA’S got a special place in my heart. It’s the source of one of those strange drinking stories that are told in a spirit of humour despite the circumstances, the kind you laugh at but don’t dwell too deeply on. That tale’s located at an intersection of football, politics and poverty. Back in the spring of 2013, I went to Albania for an academic conference. I was staying in the capital Tirana and on my first evening there, I headed out to explore the city. On my travels, I went into a bar, where they were showing the Champions League semi-final between Real Madrid and Borussia Dortmund. Over a beer, I got gripped by the battle where Madrid, being 4-1 down from the first leg, attacked all-out, having nothing to lose.

Having a conference to attend in the morning, I left at half-time, heading back to my hotel. Getting there, they’d no televised access to the game so recommended another bar down the street. When I got there, the second half was just starting. After ordering a beer I sat down. Unbeknown to me I’d sat beside a group that included the bar owner and a Turkish barber with an attractive brunette teenager passed off as ‘his daughter.’ This group appeared delighted at having an exotic visitor. In their company, I soon learned that Irish and Albanians share a common passion for chat and for football. Put the two together, and we’d be joint World champions at conversing about the beautiful game.

We kept chatting, losing track of time as the game progressed in the background. Before I knew it, Real had pulled two goals back, almost denying Jurgen Klopp’s exciting Dortmund team the more romantic story of a first Champion’s League final. Thankfully the Germans survived the Spanish onslaught. The game ended in a 4-3 aggregate victory and when the football was done, the post-match analysis began. By then, the people in my company had bought me several bottles of beer. They kept coming, without me getting time to buy a round back, as the Irish always must.

Very soon, the pub had emptied. There was just me, three men and a daughter in denim shorts in a scene like Sky Studio meets Rovers Return, a couple of hours after a Manchester derby. It was at this point that a young barman came to sit at our table. Somewhere in the midst of discussing something such as Karim Benzema’s goal, this young man interjected into our conversation. Very directly, he asked me how much I was going to pay them to sleep with the girl, though not as politely. Assuming it was a joke at first, I sat blinking in the light. Never mind the moral objection to the idea, I was shocked that everything positive I’d seen so far had been knocked for six with this proposal.

I sat there dumb, as the young man stared with the intensity of soldiers from the early 90s when Yugoslavia’s fragmentation provided daily pornography of war on our screens. Staying composed, I protested that I was here for a conference. At this stage, the lad pointed out that I’d sat around drinking their beers, suggesting interest in something else. All westerners came to Albania for one thing apparently. Now, at this point, the sensible option would be to have apologised and hot-footed it out of there straight away. But incredibly, I hulked into a social scientist, giving them a lecture on the history and national self-confidence, citing Ireland’s 20th-century rise from the ashes. I then castigated them for being such poor ambassadors for a country with so much potential and playing up to stereotypes that gave Albania a bad press.

By now, the look on the three lads’ faces was that of thinking ‘of all the foreigners that had to walk into all the bars of Tirana on all the Tuesday nights of 2013, it had to be this Irish bollocks*.’

(*in Albanian, obviously).

There even came a point at which I went all WB Yeats on them, asking the actual price at which they were willing to sell the soul of their nation, in the metaphorical figure of the daughter in denim shorts. At this stage, they realised I could only have been set loose from an asylum or a university. They began to laugh and joke and went back to talking football. Shortly after midnight, I left and headed back to my hotel, but not before they’d invited me back for more banter the following evening when Barcelona were up against Bayern Munich. The next morning I woke up about half-past six, thinking ‘Holy Christ, did all that happen?’

I reckon it was supposed to be a sting before my twist in the tale. The whole thing had been more comedic than dangerous but still somehow sad, most of all for the young woman baited like that. I never went back to the bar and that group didn’t come to the conference where I gave a presentation on symbols and identities in Northern Ireland. Staying out of pubs for the rest of my time there, I wandered the streets on spring evenings, discovering a place like nowhere else in Europe. One evening, for example, I watched a world of people in Porsches held up at traffic lights by a farmer leading his sheep to drink on the banks of the city’s river. Albania’s still developing but it’s a place with a history shaped by its position on the map of Europe, standing at a crossroads between Empires. In Tirana, I found a multicultural city where centuries blend into one another with a combination of churches and coffee shops, mosques and menswear stores. It’s said that you find the best genes in such places where different races have met and mingled over centuries.

Maybe that’s why so many fine footballers have been born in this part of the world, extending out towards the former Yugoslavia. If Albania had a slightly different history in the 20th century or found a Jack Charlton of the 21st century, they might now have a very different lineup. Half the Swiss team appears to have Albanian ancestry, including Premier League stars Granit Xhaka and Xherdan Shaqiri. Then there are others such as Adnan Januzaj who plays for Belgium and Real Sociedad, having failed to make the grade at Manchester United despite a lot of youthful promise. Added to that, the Albanian team itself, at present, has a host of decent players starring in some of Europe’s top leagues. The country’s in line for membership of the EU too at some point in the next decade, alongside North Macedonia, so even more of its players are likely to filter through to the continent’s big leagues in Germany, Italy and Spain.

There’s a lot more to Albania than the impression created by those guys in the football bar who gave me a strange story for a souvenir. That place, those events and that girl are like pictures in a fridge magnet photo frame. Such things happen in developing societies, especially when the greatest road to opportunity lies on the way out of the country. Many people of Albanian ethnicity left their homelands in the late twentieth century because of political turmoil, ranging from dictatorship to the collapse of Yugoslavia. For a long time, the Irish were in exactly the same boat, or coffin ships in many cases. Thanks to EU membership and economic stability, Ireland changed from exporter to importer of people.

Some of those who migrated to Ireland have been Albanian or Kosovar. They have integrated into the society and brought up their families there. Those kids today are as Irish as Declan Rice, Jack Grealish and Harry Kane are English. They’re the face of the multicultural Ireland that has emerged out of Britain’s shadow. They’re as Irish as anyone whose parents were born in Cork or Connemara. At the same time, the Irish emigrant experience has created a unique psyche when it comes to the contentious question of ‘where you’re from.’ Just as Jack Grealish or Declan Rice can be British with proud Irish roots or Joe Biden claims to be American and Irish, you can be Irish and proud of your roots elsewhere. And these Albanian-Irish lads might be part of a different Irish generation that puts the pride back in their country’s football team.

Recently, when the Republic of Ireland lost 1-0 to Luxembourg in a World Cup qualifier, it felt like a final nail in the coffin of where they’d once been. This was a far cry from the halcyon days of Jack Charlton taking his team to see the Pope in Rome or even Roy Keane in Saipan where he so memorably lamented Ireland’s lack of ambition. This was not even the Ireland of the 1980s that had the likes of Liam Brady and Frank Stapleton but never the organisation to actually qualify for anything. This felt like a slow descent into the anonymity of Europe’s lower ranks. But amongst the underage levels of Irish football, there are reasons to be hopeful.

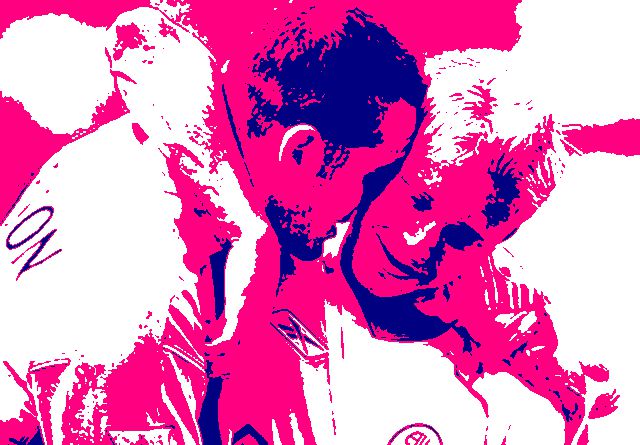

The Irish U-17 team is one of the hottest prospects in Europe right now, with such young stars as Kevin Zefi and Rocco Vata at the heart of that. Recently, 16-year-old Zefi has joined Inter Milan’s youth system, partly as a lesser-known consequence of Brexit, where it’s now harder for underage players to cross the sea to England as so many used to do. That aside, there are echoes of Liam Brady in this lad’s move to Italy and his performances to date have echoes of a young Brady too.

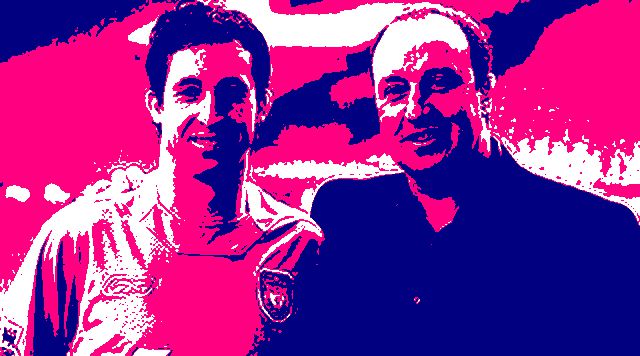

Rocco Vata is plying his trade somewhere that might be seen as less exotic though closer to Irish hearts. In that regard he already has a head start anyway, being the son of Glasgow Celtic legend, Rudi Vata. He was one of Albania’s first footballing émigrés at Parkhead, where Rocco now too has signed up, playing in midfield. Justin Ferijaz, another midfielder, still playing in the domestic League of Ireland, is also of Albanian heritage. Leo Gaxha is another of the same heritage and indisputably Irish, a Kerryman who is a couple of years above these lads and already starring as a striker with Sheffield United’s youth academy. Self-styled in the mould of Robbie Keane, he’s one to watch out for in the next few years.

However, it’s not just young Irish players of Albanian heritage who are rising through the ranks. At underage levels, squads are composed of young players reflective of today’s progressive, multicultural Ireland. Where the country once relied on the children of Irish emigrants for a taste of success, today it’s partly relying on the children of its own immigrants. There’s still a lot to be done though. Some might say the governance of Irish football over these past few decades has had echoes of Albania too. But, having told the story of one lecture, I’m not going to attempt another. Suffice to say that Albania might soon have a special place in more Irish hearts than mine, and that’s something we can all buy into.

Paul Breen is a university lecturer and author of The Charlton Men and promises not to give you a lecture if you suggest purchasing his book.